For centuries, supersessionism—the doctrine that the Church has replaced Israel in God’s covenantal plan—has distorted Christianity’s identity and its relationship with Judaism. This false teaching, as framed and institutionalized by Christian tradition, not only misrepresents the Hebrew Scriptures but also undermines the very mission of the Messiah. Christianity, at its core, was never meant to be a new religion severed from Israel; rather, it was a renewal of God’s promises, with the Messiah as the Netzer—the Branch—growing from within the covenant, not replacing it.

To understand the error of supersessionism, we must return to the prophetic vision of the Messiah found in the Hebrew Scriptures. Isaiah 11:1 declares, “A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse; from his roots, a Netzer (Branch) will bear fruit.” This image of the Messiah as the Netzer signifies continuity, not abandonment. He does not supplant Israel but emerges from its very root, bringing forth new life while remaining firmly planted in the soil of the covenant. If the root remains, then the promises to Israel remain. Supersessionism, by contrast, imagines a scenario in which the root is discarded and replaced—yet if that were the case, the Messiah himself would have no legitimacy.

The significance of Netzer extends beyond prophecy; it directly connects to the term Notzrim, which in Hebrew refers both to watchmen and, in later Jewish usage, to Christians. Jeremiah 31:6 speaks of a time when the Notzrim will cry out from the hills of Ephraim, calling people to return to Zion. The role of the watchmen was always one of preservation and restoration, not usurpation. However, just as Israel’s ancient watchmen failed to guard the covenant in 2 Kings 17:9, later theological traditions distorted this mission—shifting from a faith that calls people to covenant faithfulness to one that claims to replace the very people to whom the covenant was given.

When the New Testament calls Jesus a Natzrati (Nazarene) in Matthew 2:23, it does more than associate him with a town. It ties him linguistically to the Netzer prophecy and conceptually to the Notzrim—the watchmen of Israel. His mission was not to establish a separate religious identity but to bring renewal and restoration within Israel’s covenant. He explicitly declared in Matthew 5:17-19 that he did not come to abolish the Torah but to fulfill it, and his earliest followers continued worshiping in the Temple, observing Torah, and identifying as Jews. However, as the Church distanced itself from its Jewish roots, it abandoned this foundational understanding, constructing a theology that not only detached itself from Israel’s root but positioned itself against it.

Paul’s teachings in Romans 11 make the rejection of supersessionism inescapable. He describes Israel as the natural branches of an olive tree, with Gentile believers as wild branches grafted in. His warning is clear: “Do not boast over the branches… you do not support the root, but the root supports you.” The very idea that Israel has been replaced contradicts Paul’s central argument: the inclusion of Gentiles does not mean the exclusion of Israel. If Israel were truly rejected, the root itself would be dead, and with it, the entire tree—including Christianity. Supersessionism, in effect, saws off the very branch on which the faith rests.

Much of the theological confusion stems from a misunderstanding of the New Covenant. Many assume that it abolishes the Sinai Covenant, yet Jeremiah 31:31-34 states otherwise. The New Covenant is made with the house of Israel and Judah, not a separate entity called “the Church.” Its purpose is to write the Torah upon the hearts of Israel, not discard it. Yet, we often assume that Jesus’ mission was solely to inaugurate this renewal—not to establish a rival covenant, but to call Israel back to faithfulness while extending the invitation to the nations.

This is true, but we must remember that the New Covenant was first spoken to Torah-observant exiles five centuries before Jesus of Nazareth. It was always meant to be a covenant of transformation from within, not one of coercion—a renewal that would work from the inside out, inscribing the Torah upon the hearts of Israel rather than abolishing it. A proper understanding of the New Covenant reveals that it is not about replacement but expansion—a restoration of Israel with an opening for the Gentiles to join, not to replace.

Christianity and Islam both emerged as proselyte faiths, calling people out of ungodliness and into covenant with God. However, they developed fundamentally different approaches to religious life: Christianity emphasized doctrine over practice, whereas Islam imposed law as the foundation of faith.

Christianity, in its break from Judaism, moved away from Torah observance and structured law, shifting toward a propositional faith centered on belief rather than communal obligation. This created a dogmatic trajectory, where accepting doctrine—believing in Jesus—became the core of faith, rather than living within a covenantal legal system. Faith became an internal conviction rather than an external discipline, leading Christianity to define holiness in terms of personal morality rather than communal law.

Islam, by contrast, embraced a top-down legal system, codifying divine law (sharia) as the governing structure of society. While Christianity prioritized belief as the key to salvation, Islam insisted on legal compliance—where faith was demonstrated through submission to divine law rather than internal conviction alone. This resulted in a religion where the state and legal system enforce righteousness, in contrast to Christianity’s approach, where faith is largely a matter of personal conviction.

Thus, while post-Reformational Christianity internalized faith to the extent that it became disconnected from legal observance, Islam took the opposite approach, externalizing faith through social and legal enforcement. Both diverged from the Torah-based model, where faith and practice were inseparable, forming a covenantal system in which belief was expressed through observance. In modernity, this separation gave rise to ethics as an abstract construct, leading to confusion over the historical and covenantal foundations of faith, obscuring Christianity’s deep-rooted connection to Jewish legal and moral tradition.

Beyond theology, supersessionism has had devastating historical consequences, shaping not only religious doctrine but also fueling the trajectory of antisemitism. At its core, antisemitism is not merely hostility toward Jews as a people but opposition to HaShem (The Lord, literally The Name) Himself—a rejection of the divine covenant and the revelation given through Israel. To be anti-Jewish is to be anti-Torah, and to be anti-Torah is to be anti-HaShem. Thus, antisemitism, in all its forms, is ultimately a revolt against the authority of God’s covenant—an attempt to erase the people through whom He made His name known.

By advancing the idea that Israel was cast off, supersessionist theology legitimized centuries of Christian antisemitism and, to a lesser extent, Islamic persecution—resulting in forced conversions, pogroms, The Holocaust and discriminatory laws aimed at dismantling Jewish identity and suppressing Torah observance. Rather than embracing their role as the Notzrim—watchmen preserving God’s covenant—Christian and Islamic traditions instead became agents of erasure, marginalizing and persecuting the very people through whom God’s covenant was revealed.

In modern times, this supersessionist mindset has evolved into a secularized form of antisemitism, one that no longer operates solely on religious terms but instead reframes Jewish identity as cultural through genetics. The false claim that Jews—particularly Ashkenazi Jews—are simply a genetic relatives to the current inhabitants of Palestine is disproven by a simple DNA test which are outlawed in the State of Israel, rather than a covenantal people bound to Torah and HaShem, this has fueled new narratives of Jewish dispossession and delegitimization.

Such a revisionist framing denies Israel’s biblical and historical legitimacy as a religious-nation, recasting it as a colonial enterprise rather than the fulfillment of religious prophetic restoration as through a spiritual Zionism. On the other hand, modern antisemitism mirrors ancient supersessionism, insisting that Jews are either obsolete as a people or impostors with no rightful claim to their covenantal inheritance, which I do not hold. Nevertheless, this reframing through political Zionism is most problematic, as many Jewish groups like the Charedi have protested such a move of occupying the land in such a secular militaristic way for many years.

Therefore such realites require discerment and calls Christians toward a prophetic voice of peace and reconciliation among Abraham’s children an we know who the prince of peace (Yeshua sar Haphanim) for He is found in the Mazor prayer books of the Chardali (nationalists) unless they have an Art Scroll publishcation were He is edited out.

If Christianity is to be true to its calling, it must reject this distortion and return to its original role as a true Jewish-led, covenantal movement—one that calls the nations into holiness through Israel’s Messiah, not apart from him. Islam, by contrast, faces an even greater challenge in such acceptance, as it has historically positioned itself not as a continuation of Israel’s covenant but as a replacement of it. Until both Christianity and Islam confront their deep-seated supersessionist assumptions, they will remain complicit in the ongoing erasure of Jewish covenantal identity—whether through religious doctrine, political narratives, or secularized antisemitism, which, at its root, is nothing less than opposition to The Lord Jesus Christ Himself.

Ultimately, supersessionism fails because it misunderstands the Messiah Himself. The Netzer does not replace the tree—he is new growth from within it. The Notzrim are not usurpers of Israel’s covenant but its watchmen, ensuring its fulfillment. The Gospel does not sever Israel’s roots but calls Jew and Gentile alike into the righteousness the covenant demands.

To be true to the Messiah, Christianity must return to its foundations and reject the false doctrine of replacement. Only then can it rightly honor the Netzer of David—the Messiah who restores, not replaces, Israel into Am Yisrael, the Ummah, and, as Ephesians declares, the Commonwealth.

Ephesians 2:19 (ESV):

“So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God.”

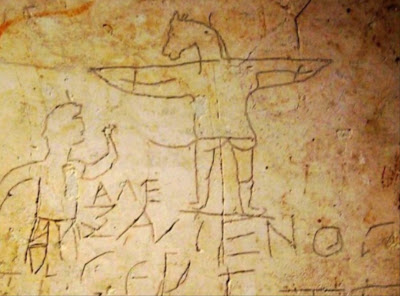

My Ana-Baptist Great Grandfather’s Grave

once in Bavaria after being a refugee in old age from Eastern Europe