Rome captivates the senses, with Matthew 16:13-20 gleaming in gold from Peru along the towering perimeter of the Vatican’s Basilica, beneath Michelangelo’s majestic dome and Pietà at the entrance. But have Evangelicals truly grasped the significance of this passage?

Many interpret Simon Cephas’ confession as the primary divide between Rome and Protestantism. However, this reading overlooks a crucial Hebrew perspective—specifically, the insertion of Petter (Petra), a pun frequently found in Talmudic discourse regarding Cephas as “the rock.” This imagery draws from the Maccabean-era absorption of Edom, Petra, and the Nabataeans—now embodied in the Herodians and Rome itself.

When Simon Peter, a redeemed lost sheep of Israel, stood at Caesarea Philippi, he was not confronting mere contextualization but full-blown syncretism, surrounded by pagan temples at the base of Mount Hermon—the highest peak in the Holy Land. This mountain, another “great rock,” plays a significant role in Jewish apocryphal traditions, particularly in the Books of Enoch, where it takes on a mystical life of its own.

God’s revelation has always addressed humanity’s struggle with sin and idolatry—from Abraham’s apostate origins in Ur of the Chaldees to the religious empires of Egypt, Babylon, and Persia. This extends to Esau’s brother-in-law, Nebaioth (Genesis 25, 28, 36), whose name means prophet and who is associated with the Petter Chamor—the firstborn of Abraham’s son, Ishmael. Too often cast as an “evil seed,” Ishmael’s lineage actually represents a missiological trajectory for redeeming the erev rav (the “mixed multitude”)—from which the term Arab derives.

The inheritance of Isaac, however, carries the divine oracles forward. In Galatians 4, Paul uses Hagar and the Heavenly Jerusalem to illustrate the ultimate destination of the seed of promise, emphasizing its availability to all people. This theme is reinforced in Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem—riding on a donkey.

Unlike in the West, where donkeys became symbols of stupidity, these creatures were prized in Jewish tradition for their intelligence and reliability as travel companions. In fact, the donkey is the only contaminated (tumah, not “unclean”) animal that is holy enough for Pidyon haBen (the redemption of the firstborn) as detailed in Exodus 13.

Thus, when Jesus spoke the Petter pun on Cephas, he was identifying Peter—once a hardened sinner (Luke 5:8)—as one made holy through exemption as a Petter (firstborn), set apart for the lost sheep of the edah (congregation). This transformation establishes Peter as one of the pillars of the New Testament church.

Yet, this does not negate Paul’s rebuke of Peter for his ethnocentric tendencies (Galatians 2). While Peter understood his role in bringing the Gospel to Cornelius (Acts 10), his withdrawal from table fellowship with Gentiles in Antioch suggests an ongoing struggle with Jewish Qahal (assembly) observance.

His actions—possibly an attempt to avoid “Judaizing”—illustrate the perpetual tension between Jewish discipleship (Talmidim) and the inclusion of Gentiles. This may also shed light on Peter’s reference to the “heavy yoke” in Acts 15. Such nuanced theological developments in the New Testament were later co-opted by Christendom in ways that obscure their original Jewish context.

The medieval Talmudic commentator Rashi (1100s) provides an intriguing insight, suggesting that the Apostles intentionally “influenced their culture” to steer the Notzri (Christian) faith away from Judaism, shaping it into a Messianic Noahide framework. Yet, Rashi maintains that they were not heretics but acted for the benefit of the Jewish people.

Further reinforcing this concept, the Hebrew word Petur—meaning “redeemed firstborn”—also carries the meaning of “exempt.” This description fits the role of a Petter Chamor, a Baal Teshuva (one who returns to faith) guiding pilgrim Messianic Noahides, such as Cornelius. In this sense, Simon bar Jonah carried forward the tradition of divine revelation to the nations.

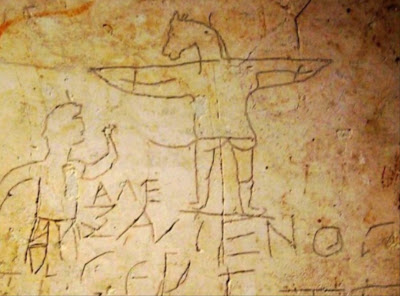

Perhaps the most enduring testament to Simon Peter’s presence in Rome is not the Basilica that bears his name, but rather the Alexamenos Graffito on Palatine Hill—an ancient depiction of a man worshiping a crucified figure with a donkey’s head.

Scholars argue that this was meant to mock early Christians, likening their God to an Egyptian demiurge. However, the donkey—an unclean yet kosher animal—recalls the ways Jewish missiology functioned in the Tanakh and Septuagint, using allegorical animals as teaching devices.

Why does the pattern of the cross

appear etched upon the donkey’s back?