Jesus rode into Jerusalem

on a donkey,

and the crowd shouted

“Hosanna! Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord!”

(Matthew 21:9)

But did they really understand what was happening? Or DO WE?

For many, this was the arrival of a political messiah, a king who would drive out the Romans and restore Jewish sovereignty. Others were skeptical, unsure whether Jesus truly embodied the hopes of Israel.

Today, the same confusion remains. What does it mean to be Israel? Who belongs to God’s covenant people? And how does the modern discussion of Jewish identity align with the biblical vision?

Beyond Bloodlines: Rethinking Jewish Identity

In both Jewish and Christian circles, identity is often reduced to genetics, halakha, or politics. Some define Jewishness purely by bloodline, while others insist on strict rabbinic adherence. Many Christians, influenced by dispensationalist theology, see modern Israel as a prophetic clock, assuming that national events must align with end-times prophecy.

But biblical identity has never been that simple. Neither the way Dispensationaism defines prophecy.

The Torah and the history of Israel reveal a more complex and covenantal reality—one that Jesus Himself came to fulfill.

Jewish Identity Has Never Been Only About Bloodline nor Cultural Gene Pool

The reality is that Jewishness has always been a combination

of lineage, law, and covenant.

It has never been a purely racial or national identity.

The 1948 establishment of Israel is the direct fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Jewish identity is still defined by ethnicity and statehood rather than covenant faithfulness. The final national repentance of Israel must occur in a set sequence, leading to the return of Jesus.

However, the Bible presents a more profound and theological vision of Israel’s restoration:

Israel’s return is always tied to repentance and renewal (Deuteronomy 30:1-6).

Jesus is already gathering Israel—not just politically, but spiritually—through both Jews and Gentiles under His kingship (Acts 15:16-17, Romans 11).

The New Covenant does not replace Israel but brings it to its intended fulfillment—to be a light to the nations through Messiah.

This means that instead of treating Israel as a mere sign, we must recognize her covenantal purpose—a mission that is fulfilled in and through Jesus, not apart from Him.

What Does It Mean to Be Israel Today?

In light of all this, we must rethink how we understand Jewish identity in the context of biblical fulfillment.

Jewishness is not just genetics or political statehood—it is covenantal faithfulness. The Messiah restores and completes Israel’s purpose—not by erasing Jewish identity, but by fulfilling it.

The modern state of Israel, while historically significant, is not necessarily the final fulfillment of prophecy—the ultimate restoration is spiritual and covenantal.

Conclusion: A Covenant Restored in Messiah

The triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem was more than a political moment. It was the proclamation that the true restoration of Israel had begun—not through military conquest, but through the fulfillment of the covenant in Him.

Israel’s calling is not merely national, ethnic, or political—it is a divine mission that finds its fulfillment in the King who rode in on a donkey.

It is time to move beyond simplistic ideas of Jewish identity and prophecy and return to the biblical framework—one where Jesus, as the King and High Priest of Israel, brings the covenant to its true completion.

This is the true fulfillment of Israel’s mission—not a return to ethnic exclusivity, but an expansion of the covenant that upholds Israel’s unique role while inviting all nations into the redemption God has promised.

But biblical identity has never been that simple. Neither the way Dispensationaism defines prophecy.

The Torah and the history of Israel reveal a more complex and covenantal reality—one that Jesus Himself came to fulfill.

Jewish Identity Has Never Been Only About Bloodline nor Cultural Gene Pool

Many assume that Jewish identity is strictly hereditary, but this is not the case. Even in ancient Israel, covenantal participation was as important as ancestry.

Caleb, a Kenizzite (Numbers 32:12), became a leader in Israel despite not being ethnically Israelite.

Ruth, a Moabite, became an ancestor of King David through her faith and covenant loyalty.

Elijah (the prophet who confronted Ahab Jezabel and the prophets of Baal) was a Tishbite (Tishbi) could be related to the Hebrew root “shavah” (תָּשַׁב) meaning “sojourner” or “settler”—implying he was a Ger Toshav (resident alien) rather than a native-born Israelite.

The “mixed multitude” (Erev Rav where we get the name Arab) in Exodus 12:38 left Egypt alongside Israel and became part of the covenant community.

By the Second Temple period, Jewish identity had developed into a more legal and social structure, divided into categories:

Yikoth A – Kohanim (Priests): Those descended from Aaron, with strict genealogical requirements. Remnants of the Kohanim lineage can still be traced within Jewish gene pools today, maintaining their historical and ritual significance.

Yikoth B – This includes Jews by faith and practice, incorporating Gerim (proselytes)—where the generic name “Hagar” originates—and other converts, such as Edomites and Nabateans, who were integrated into Jewish identity under Hasmonean rule, even figures like Herod. This category extends far back, arguably to Seth and the daughters of Cain, indicating a longstanding tradition of integration before the people of Israel. For example the Anshei HaShem in the pre-Noah world and the Gibborim, the mighty men of old. This means that Noah’s son Shem was not the founder of a genetic lineage or blood line for he was named after the way Jews say the Lord, HaShem = The Name

Yikoth C – Mamzerim, Afsuf (Mixed Populations), and Erev Rav: Groups that, while marginalized, were still part of Israel’s broader history — if you are Christian Believer in Mashiach or a Muslim beleiver in ISA as the Mosiach like the Sabians, and you live as disciple (Talmudim) and obey Acts 15 and Sura 42 in the Quran — one may already be in Yikoth B. Then Judaism considers you a Messianc Hebrew or Noahide. Why was such information in the writings of Augustine of Hippo? This will challenge many preconceptions you may have long held—and perhaps even held too tightly.

This reconfiguration of identity does not simply shift perspectives; it disrupts inherited assumptions and offers a radical way to reimagine the future. It breaks down artificial barriers, moving beyond ethnic lineage and re-centering covenantal belonging on divine redemption rather than mere genealogy.

Caleb, a Kenizzite (Numbers 32:12), became a leader in Israel despite not being ethnically Israelite.

Ruth, a Moabite, became an ancestor of King David through her faith and covenant loyalty.

Elijah (the prophet who confronted Ahab Jezabel and the prophets of Baal) was a Tishbite (Tishbi) could be related to the Hebrew root “shavah” (תָּשַׁב) meaning “sojourner” or “settler”—implying he was a Ger Toshav (resident alien) rather than a native-born Israelite.

The “mixed multitude” (Erev Rav where we get the name Arab) in Exodus 12:38 left Egypt alongside Israel and became part of the covenant community.

By the Second Temple period, Jewish identity had developed into a more legal and social structure, divided into categories:

Yikoth A – Kohanim (Priests): Those descended from Aaron, with strict genealogical requirements. Remnants of the Kohanim lineage can still be traced within Jewish gene pools today, maintaining their historical and ritual significance.

Yikoth B – This includes Jews by faith and practice, incorporating Gerim (proselytes)—where the generic name “Hagar” originates—and other converts, such as Edomites and Nabateans, who were integrated into Jewish identity under Hasmonean rule, even figures like Herod. This category extends far back, arguably to Seth and the daughters of Cain, indicating a longstanding tradition of integration before the people of Israel. For example the Anshei HaShem in the pre-Noah world and the Gibborim, the mighty men of old. This means that Noah’s son Shem was not the founder of a genetic lineage or blood line for he was named after the way Jews say the Lord, HaShem = The Name

Yikoth C – Mamzerim, Afsuf (Mixed Populations), and Erev Rav: Groups that, while marginalized, were still part of Israel’s broader history — if you are Christian Believer in Mashiach or a Muslim beleiver in ISA as the Mosiach like the Sabians, and you live as disciple (Talmudim) and obey Acts 15 and Sura 42 in the Quran — one may already be in Yikoth B. Then Judaism considers you a Messianc Hebrew or Noahide. Why was such information in the writings of Augustine of Hippo? This will challenge many preconceptions you may have long held—and perhaps even held too tightly.

This reconfiguration of identity does not simply shift perspectives; it disrupts inherited assumptions and offers a radical way to reimagine the future. It breaks down artificial barriers, moving beyond ethnic lineage and re-centering covenantal belonging on divine redemption rather than mere genealogy.

The reality is that Jewishness has always been a combination

of lineage, law, and covenant.

It has never been a purely racial or national identity.

Jesus and the Redemption of Israel’s Divided Lineage

If Jewish identity was fragmented by different social and legal categories, Jesus’ mission took on an even greater significance.

His Davidic bloodline (Matthew 1, Luke 3) confirmed His legal right to be King.

His Nazarene identity connected Him to the lost Northern Kingdom—the people who had “done evil in the sight of the Lord” and were scattered.

His baptism by John was not about personal repentance, but a Gula Chumrah (redemptive stringency), identifying with and redeeming the fallen northern bloodline.

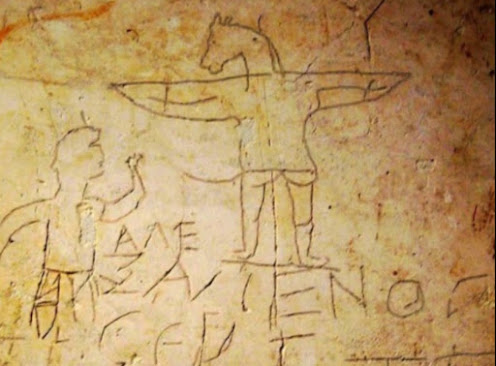

His triumphal entry on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9) was not just a messianic Mashiach sign—it was also a fulfillment of the firstborn redemption (Pidyon HaBen) of Exodus 13, symbolizing His role as the rightful heir and redeemer of Israel.

Thus, Jesus’ mission was not merely to establish a new religion, but to restore the covenantal unity of Israel—both Judah and the lost tribes as Jeremiah foretold.

Hebrews and the End of Lineage-Based Priesthood

His Davidic bloodline (Matthew 1, Luke 3) confirmed His legal right to be King.

His Nazarene identity connected Him to the lost Northern Kingdom—the people who had “done evil in the sight of the Lord” and were scattered.

His baptism by John was not about personal repentance, but a Gula Chumrah (redemptive stringency), identifying with and redeeming the fallen northern bloodline.

His triumphal entry on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9) was not just a messianic Mashiach sign—it was also a fulfillment of the firstborn redemption (Pidyon HaBen) of Exodus 13, symbolizing His role as the rightful heir and redeemer of Israel.

Thus, Jesus’ mission was not merely to establish a new religion, but to restore the covenantal unity of Israel—both Judah and the lost tribes as Jeremiah foretold.

Hebrews and the End of Lineage-Based Priesthood

The Book of Hebrews explains how Jesus fulfills Israel’s calling—not by replacing it, but by completing it.

Hebrews 7 declares that Jesus is the eternal High Priest, surpassing the Levitical system. This means that Jewish identity is no longer bound to genealogical priesthood but to faithfulness in Messiah.

Hebrews 9-10 shows that Jesus fulfills the sacrificial system, not by negating it, but by bringing it to completion in a way that applies universally to both Jews and Gentiles.

This means that true Jewish restoration is not just a return to the land, but a return to the covenant—a covenant fulfilled in Messiah.

Hebrews 7 declares that Jesus is the eternal High Priest, surpassing the Levitical system. This means that Jewish identity is no longer bound to genealogical priesthood but to faithfulness in Messiah.

Hebrews 9-10 shows that Jesus fulfills the sacrificial system, not by negating it, but by bringing it to completion in a way that applies universally to both Jews and Gentiles.

This means that true Jewish restoration is not just a return to the land, but a return to the covenant—a covenant fulfilled in Messiah.

The Dispensationalist Fallacy: Israel as a Political Sign

Many modern Christians—especially those shaped by dispensationalist theology—view Israel primarily through a political and eschatological lens.

They assume that:

They assume that:

The 1948 establishment of Israel is the direct fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Jewish identity is still defined by ethnicity and statehood rather than covenant faithfulness. The final national repentance of Israel must occur in a set sequence, leading to the return of Jesus.

However, the Bible presents a more profound and theological vision of Israel’s restoration:

Israel’s return is always tied to repentance and renewal (Deuteronomy 30:1-6).

Jesus is already gathering Israel—not just politically, but spiritually—through both Jews and Gentiles under His kingship (Acts 15:16-17, Romans 11).

The New Covenant does not replace Israel but brings it to its intended fulfillment—to be a light to the nations through Messiah.

This means that instead of treating Israel as a mere sign, we must recognize her covenantal purpose—a mission that is fulfilled in and through Jesus, not apart from Him.

What Does It Mean to Be Israel Today?

In light of all this, we must rethink how we understand Jewish identity in the context of biblical fulfillment.

Jewishness is not just genetics or political statehood—it is covenantal faithfulness. The Messiah restores and completes Israel’s purpose—not by erasing Jewish identity, but by fulfilling it.

The modern state of Israel, while historically significant, is not necessarily the final fulfillment of prophecy—the ultimate restoration is spiritual and covenantal.

Conclusion: A Covenant Restored in Messiah

The triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem was more than a political moment. It was the proclamation that the true restoration of Israel had begun—not through military conquest, but through the fulfillment of the covenant in Him.

Israel’s calling is not merely national, ethnic, or political—it is a divine mission that finds its fulfillment in the King who rode in on a donkey.

It is time to move beyond simplistic ideas of Jewish identity and prophecy and return to the biblical framework—one where Jesus, as the King and High Priest of Israel, brings the covenant to its true completion.

This is the true fulfillment of Israel’s mission—not a return to ethnic exclusivity, but an expansion of the covenant that upholds Israel’s unique role while inviting all nations into the redemption God has promised.