The Talmud tells a striking story: Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, longing to know when the Messiah will come, meets the prophet Elijah and asks, “Where is he?” Elijah replies, “He is sitting at the gates of Rome.”

Rabbi Yehoshua goes to find him and sees the Messiah among the afflicted, tending to his wounds. Unlike the others, who unwrap and rewrap all their bandages at once, the Messiah carefully binds his wounds one at a time. The rabbi asks, “When will you come, my master?” The Messiah replies, “Today.”

Overjoyed, Rabbi Yehoshua returns to Elijah, expecting the Messiah’s arrival. But nothing happens. He goes back to Elijah, confused: “He lied to me! He said he would come today, but he did not.”

Elijah explains, “No, he meant what is written in the Psalms: ‘Today—if you hear His voice’ (Psalm 95:7).”

This brief but profound exchange reveals the paradox of redemption: the Messiah is already present, already tending to the world’s wounds, yet his full revelation depends on whether people will recognize him. He is not hidden in a distant realm but sits at the very gates of empire—near, yet unrecognized. This image is not just a reflection on ancient Jewish messianism; it is an affirmation of Torat Edom, a framework for understanding Christendom’s place in the unfolding drama of redemption.

Edom and the Hidden Messiah

In Jewish thought, Edom is not just a nation but a symbol of empire, exile, and the transformation of revelation into power. Rome, as Edom’s historical and theological successor, stands as both the preserver and distorter of divine truth. It is the seat of imperial Christendom, a system that took the Jewish Messiah and reinterpreted him through the lens of conquest and hierarchy. And yet, the Messiah himself is not enthroned within Rome—he waits outside its gates, tending to wounds rather than ruling from a palace.

This paradox affirms Torat Edom: Christendom, for all its distortions, still carries echoes of the Messiah. The Messiah is present in Rome’s story, but not yet fully revealed. He remains at the threshold, waiting for the day when he will be recognized for who he truly is.

Binding the Wounds of the World

The Talmud’s detail that the Messiah tends to his wounds one at a time is not incidental—it is deeply symbolic. Unlike others who remove all their bandages at once, he heals patiently, carefully, always prepared to rise at a moment’s notice. This speaks to the nature of redemption:

The world’s wounds are not healed in an instant but through a slow, ongoing process. The Messiah is already at work, binding what is broken, but the restoration is not yet complete.Healing and redemption require participation. The Messiah is not waiting for power, violence, or an imperial declaration—he is waiting to be heard. The moment of redemption is not determined by force but by recognition.

Christendom or Christianity too, is wounded. It has carried the name of the Messiah but often in ways that obscure his true nature. It built thrones where he had no throne, wielded power where he had renounced it, and mistook empire for the Kingdom of God. Yet, the Messiah still sits at its gates, tending to the very wounds history has inflicted, waiting for the moment when Christendom will recognize its own exile.

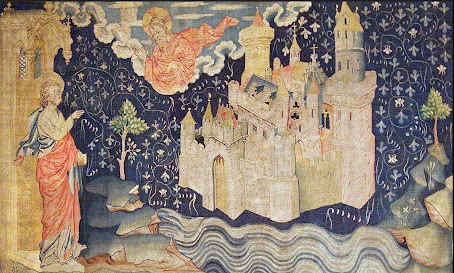

The Angers Tapestry 14th Century

The Messiah at the Threshold of the Messianic Age

The key moment in the Talmudic account is when the Messiah answers, “Today.” On the surface, this seems misleading—why didn’t he come? But his response is conditional: “Today—if you hear His voice.”

This tells us something crucial about the Messianic Age: it is not simply a future event on a divine calendar but a threshold reality—always near, always waiting, but dependent on recognition. The exile does not end through conquest or political power but through revelation.

This also corrects a fundamental mistake in Christendom’s self-understanding. The church, from its imperial days onward, assumed it was already in the Messianic Age, that the Kingdom of God had arrived in the form of ecclesiastical and political dominion. But if the Messiah still sits at the gates, it means that Rome is not the destination—it is the barrier. The world is still in exile, and the Messianic Age will only be fully realized when Christendom ceases to be Rome and begins to be Zion.

From Rome to Heavenly Zion: The Final Ascent

The Messiah at Rome’s gates tells us something fundamental: redemption does not come through perfecting empire but through transcending it. This is the true meaning of Torat Edom—Rome must hear the voice it has long ignored, not to become a better version of itself, but to recognize that it was never meant to be the final story.

Micah 4 gives the true vision of the Messianic Age:

“In the last days, the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established… and the nations shall flow to it.”

The Messiah is not waiting to establish a new Rome nor earthly Jerusalem; he is calling the nations to Heavenly Zion. He is not a king of conquest but a healer, binding the wounds of history one at a time, waiting for the world to finally listen.

The gates of Rome are open. The Messiah is at the threshold. The only question is:

Will we hear his voice? Yes!

From Individual Realization to Proclamation

The eschaton has long been imagined as an event that will one day arrive, a cosmic unveiling of divine truth at the end of time. But what if the eschaton is not merely something to be awaited, but something to be realized? What if the end of all things does not reside in a distant future but is already unfolding within the depths of human existence? To think of the eschaton in an individual and existential sense is to recognize that its arrival is not a collective spectacle but a moment of awakening within the self. It is a radical shift in being, an event in which one comes face to face with ultimate reality. Yet this realization cannot remain silent; it must be spoken. The one who experiences the eschaton is compelled to proclaim it, for truth, once encountered, demands to be given voice. This essay explores the journey from individual realization to proclamation, tracing the eschaton as a personal, existential event that insists upon being spoken into the world.

The Eschaton as Personal Awakening

To realize the eschaton is not merely to acknowledge a doctrine but to undergo a transformation. It is an awakening to the presence of the eternal in the present moment. Traditionally, eschatology has been about the future fulfillment of time, but in an existential sense, the eschaton is not bound to chronology—it is a breaking-in of ultimate reality into the now. This realization often occurs at the margins of existence: in crisis, in profound silence, in moments where the self is confronted with its own limitations. It is a recognition that what one has been waiting for has already arrived, and the weight of this truth changes everything.

For Martin Heidegger, this realization comes in the awareness of being-toward-death (Sein-zum-Tode)—the fact that our existence is finite, always already moving toward an end. This is not a reason for despair but for authenticity; the individual who lives in awareness of the end lives more fully. The eschaton, then, is the awakening to one’s own radical finitude, an invitation to live as if every moment were the last, as if eternity were already woven into time. Søren Kierkegaard speaks of this in terms of the moment (Øieblikket), the instant in which time and eternity intersect. The individual who realizes the eschaton steps into this eternal moment, no longer postponing life’s most essential decisions.

Meister Eckhart centuries earlier —the ‘Godfather’ of the fragmentation into Modernity— takes this further, arguing that God’s kingdom is already within. The eschaton is not about waiting for an external transformation; it is about undergoing an inner one. In Eckhart’s view, the one who has emptied themselves of all false attachments, who has surrendered their ego and become transparent to the divine, has already entered the eternal. The eschaton is not an event to be awaited—it is a reality to be realized. The individual who reaches this awareness is no longer bound by temporal concerns, for they have already stepped into the infinite.

Yet this realization cannot remain a solitary experience. The eschaton, once realized, demands to be proclaimed.

The Necessity of Proclamation

To encounter truth is to be placed under its weight. It is impossible to hold it in without it burning from within. The Hebrew prophet Jeremiah captures this feeling when he says,

“His word is in my heart like a burning fire, shut up in my bones. I am weary of holding it in; indeed, I cannot.”

(Jeremiah 20:9).

The one who has seen cannot remain silent. This is the tension between mysticism and proclamation—the temptation to retreat into the ineffable and yet the inescapable need to speak.

Eckhart in his Latienishe Werke throws this bomb from the Gospel of John 1:38, two disciples ask Jesus, “Ubi habitas?” (Where do you dwell? ). This is not a mere request for location—it is an existential question. Where does truth reside? Where is ultimate reality to be found? Jesus does not answer directly; instead, he invites them: “Come and see.” The eschaton is not about receiving a final, static answer—it is about entering into an experience, stepping into the unfolding revelation of the divine. And once one has seen, one is compelled to invite others: “Come and see.”

This shift from realization to proclamation is not a choice—it is an inevitability. Karl Barth describes proclamation as the event in which God speaks; it is not merely the communication of information, but the moment in which divine reality becomes audible in the world. Paul Tillich speaks of kairos, the decisive moment where eternity invades time—and to proclaim the eschaton is to bring others into this kairos.

Proclaiming the Eschaton as an Event

To proclaim the eschaton is not to deliver a doctrine but to create an event. The one who proclaims does not simply describe truth; they speak it into being. Proclamation, in this sense, is an eschatological act—it is the breaking forth of the kingdom in the very moment of speech.

Yet proclamation is costly. The one who proclaims is often met with resistance, for people do not wish to be awakened from their illusions. Kierkegaard warns that truth-tellers are rarely welcome, for they disrupt comfort and demand transformation. Eckhart notes that many will reject the message because it threatens their false self. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in his reflections on costly grace, reminds us that to proclaim the kingdom is to step into suffering, for the world resists the intrusion of the divine.

And yet, the one who has realized the eschaton has no other choice but to proclaim. Silence is not an option. The word must be spoken, not because the speaker desires it, but because it insists on being heard.

The Eschaton Must Be Spoken

The journey from realization to proclamation is the journey from awakening to responsibility. One does not experience the eschaton for themselves alone; to see is to be sent. To realize the kingdom is to become its voice, to declare that the end has already begun, that eternity is now, that the kingdom is at hand.

This is why Jesus does not answer “Ubi habitas?” with a static truth but with an invitation. The one who has seen must say to others, “Come and see.” For in the moment of proclamation, the eschaton is not merely realized—it is revealed.