The Creation account and much of Genesis are spiritual revelations rendered into physical descriptive dimensions—realities that are out of this world, but perhaps not another dimension as commonly understood. The dichotomy between nature (physis) and grace (supernatural ) has shaped Western thought, often leading to debates on certainty within Christianity, Post Maimonidean Judaism, and Islam, as they all unite in Classical Theism, not Theistic Personalism.These debates reflect humanity’s ongoing desire to understand the knowledge of good and evil and the divine image within us.

However, this pursuit is fraught with hubris, as reason and presuppositions often distort spiritual truths, keeping us bound to their binary frameworks rather than true first principles. A reexamination of these foundations is necessary, holding firmly to Biblical authority while recognizing the limits of human interpretive methods. Only through exhibiting humility can we grasp how our spiritual fall transforms physical reality.

Adam, HaAdam, and the Two Realities of Creation

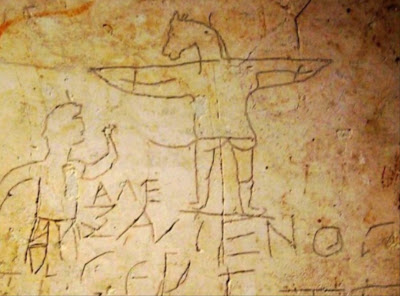

The Creation narrative in Genesis begins with HaAdam, a term distinct from the Second Adam in Genesis 4:25. This original Adam marks the revelatory beginning of the Hebrew calendar, about 6,000 years ago. The Previous HaAdam and Eve fell from the realm of Yetzirah (formation) into Assiya (action)— perhaps a spiritual descent mirrored in the “skins” they were clothed in, after a literal ‘Fall’ from another dimension? According to empirical pursuits, their offspring populated the earth, with lineages connecting with Neanderthals, as corroborated by genetic evidence. These origins, verified by data back 200,000 years, invite us to consider not just who the first humans were, but when and where they existed—a question perhaps pointing us toward the heavens, our ultimate destination? Space is the place!

Cain, Abel, and the Spiritual Re-Creation of Adam

Genesis reveals a foundational myth of fratricide in the story of Cain and Abel, reflecting broader human struggles. Cain may symbolize Homo sapiens, Abel the Neanderthals, (who knows?) both representing humanity’s fractured beginnings. However, the narrative introduces a transformative break with the birth of Seth in Genesis 4:25 which is easily missed. Nevertheless, and this is the point, this Second Adam is not HaAdam of Genesis 1–4 but a later spiritually re-created figure. Seth’s lineage is a righteous one, contrasting with the already multiplying fallen line of Cain who had seven succesive generations.

The Nephilim, or “fallen ones,” emerge from HaAdam’s corrupted lineage. They are perhaps not so much mythical giants but symbolic of spiritual and moral corruption. The “sons of God,” descendants of Seth, sought to redeem the “daughters of men,” the line of Cain, for the seed of the woman is instructive. Yet corruption persisted, eventually culminating in the flood and Noah’s preservation as a remnant of a righteousness man.

The Spiritual Image and Restoration in Christ

The original HaAdam bore the image of God but fell, requiring spiritual restoration. Jesus, the Alpha and Omega as the Second Adam, embodies this restoration, enabling worship in spirit and truth. The Nephilim, described as “fallen faces,” are potentially redeemed in Christ, who restores the divine image to humanity.

The post-Babel narrative connects the Nephilim to the concept of Jinn in Judeo-Arabic traditions, and ultimately to the term “Gentile”. The domain of the nations emerges as contextual where true spiritual transformation long for our mother above. Importantly, these corrupted lineages reflect the powers and principalities that oppose God’s sovereignty, emphasizing that the confusiong term Israel’s identity is spiritual rather than tied to any earthly nation-state that promotes racism and copies a ‘nationalism’ into distortion.

The Angel of the Lord and the Messiah’s Mission

Throughout the Old Testament, the eternal Son manifests as the Angel of the Lord, the Word, and the Name of God. The Messiah’s mission unfolds in two dimensions: Messiah ben Joseph, a suffering servant, and Messiah ben David, a conquering king yet to be fully revealed. Jesus of Nazareth fulfills the former and is widely undertood to inaugurate the latter, bridging spiritual restoration and physical reality.

In His baptism by John, Jesus submitted to the law, stepping into the role of a Ger Toshav (resident alien) to redeem the lost sheep of Israel. His genealogy in Matthew affirms His Davidic lineage, while Luke’s genealogy emphasizes His spiritual mission. This duality highlights Jesus as both the perfect human and the divine Savior.

Eschatology and the Unity of Humanity

The physical and spiritual dimensions converge in eschatology. While ethnic and cultural Jewish identity remains significant for the sake of the meta-narrative, the ultimate focus is spiritual: the New Jerusalem and the restoration of creation. Nationalisms and racial distinctions fall away in light of the Great Commission, which calls all humanity to the obedience of faith.

Fantasy interpretations, such as angel-human hybrids, distract from the simplicity of the Biblical message. The Nephilim and other elements of Genesis should be understood as symbols of spiritual realities, not as fodder for speculative mythology. The focus must remain on Jesus Christ, the fulfillment of God’s promises and the Savior of all humanity and the redeemed role.

Conclusion: Simplicity in Christ

The 66 books of the Bible provide all we need to know Christ and His plan for humanity. Apocryphal and non-canonical texts may offer historical insights, but they are secondary to the Spirit’s work in illuminating Scripture. Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah, is the answer to humanity’s deepest questions about purpose, identity, and salvation.

We are one human race, united in our need for a Savior. Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection empower believers to live out spiritual truths in the physical world. Through Him, we rediscover the divine image and participate in His story—a story that transforms both individuals and creation itself.