Granted, such futurism may seem plausible in light of current events. That is precisely why Christendom–Edom should compel us to reflect on Paul’s image of the Cultivated Olive Tree (Rom. 11:17–24). We are not to flaunt a new religion but to recognize and humbly accept our grafting into an existing covenantal reality—to become a missional people of peace and justice, rather than doctrinal warriors who interpret Romans 9–11 without the declarative action that Jesus Christ is Lord and without visibly displaying His character in the world.

The historical Esau–Edom rejection, often framed as “non-election” and extrapolated to entire ethnic or spiritual categories, is deeply flawed. It exposes the limits of theological systems that explain without understanding—the limits of reading the Bible through confining covenants rather than the Abrahamic household, the family through whom all nations are to be blessed. Any framework that divides humanity into castes of election fails to comprehend the breadth of Abraham’s promise.

If we speak of a “spiritual Israel” and seek to avoid supersessionism, then Christians themselves must be seen as the redemption of unspiritual Esau or Edom, and by extension even of so-called Messianic Jews. Nevertheless, we are all Hebrews—members of the Commonwealth of Israel (Eph. 2:12–13)—called into the same covenantal family by grace.

Why Was Esau Hated?

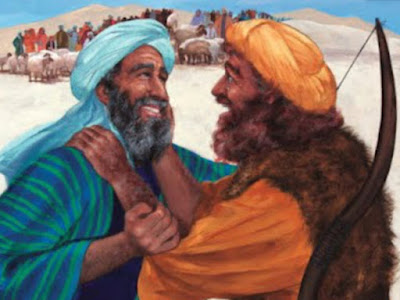

Both Malachi and Romans echo the tension of divine election and human choice. In Jewish tradition, Torah—literally instruction—depicts an unchanging reality of truth. Esau was not cursed by divine caprice but by his own choices: taking Canaanite wives, disregarding the birthright, and ultimately “living by the sword.” Yet, even in his story there is grace. Genesis 28:6–9 records that Esau sought reconciliation by marrying into Ishmael’s line—one of Ishmael’s daughters—thus rejoining Abraham’s family.

Rabbinic tradition further records that Esau’s head, severed by Chushim ben Dan, “rolled into the lap of Isaac” (Gen. Rab. 78:12). This midrash is profound: though Esau’s body—his earthly dominion—remained outside, his head, the seat of consciousness, was received into his father’s bosom. Edom means red, and in that color we glimpse redemption. For Jesus Christ—the Redeemer in crimson (Isa. 63:1–3)—fulfills Isaac’s blessing to Esau: “By your sword you shall live… and you shall serve your brother.” In Him, the grapes of wrath become the wine of salvation; the blood of judgment becomes the blood that saves.

Edom’s Prophets and the Forgotten Family

If we posit only a “spiritual Israel,” what do we make of Obadiah, Job, Eliphaz, or even Caleb—all identified by tradition as Edomites descended from “unspiritual Esau”? Their witness complicates any linear narrative of rejection. These figures—and the Jewish Midrashim that preserve their memory—reveal the gaps in our comprehension of Abraham’s entire covenant family and our tendency to idolize Jacob at Esau’s expense. Perhaps this is why the Charedim, those pacifist Jews who reject political coercion and political Zionism, embody a more faithful Jacob—one who waits upon God’s justice rather than wielding the sword like has been the history since 1948.

Paul’s Context in Romans 9–11

Paul’s discourse in Romans 9–11 must be read within this broader frame. “Jacob,” or its nationalized expression Israel, had become by Paul’s day a religio licita—a sanctioned religion within the Roman Empire—and had therefore absorbed imperial habits of exclusivity. Thus, Paul asks in Romans 10:19a, “Did Israel not understand?” Indeed, they did—but true understanding required Torah faithfulness, as modeled in Acts 15, where Esau–Edom symbolically represents the nations being welcomed in.

In Romans 10:19b, Paul cites Moses’ prophecy from Deuteronomy 32:21, reflecting on the ‘erav rav’—the mixed multitude that left Egypt. These included non-Israelites like Ephraim and Manasseh, faithful not by lineage but by obedience. “I will make you jealous by those who are not a nation; I will make you angry by a nation without understanding.” In Paul’s framing, Israel’s jealousy is provoked by outsiders—the very ones once considered “unspiritual,” whose devotion exposes Israel’s covenantal complacency.

This dynamic continues today. Simple believers in Christ—within both nationalistic Christianity and forms of Islam—often serve as unintended witnesses, provoking those bound to political or religious systems to reconsider God’s covenantal faithfulness. These are “replacement traditions” in structure, yet within them live individuals stirred by the Spirit toward the Messiah and toward mercy, even for Chiloni (secular) or Chardali (nationalist) Jews.

Torat Edom and the Red Judaism of Christ

Thus, Jesus Christ and the Christian Scriptures embody Torat Edom—a Red Judaism that opens the covenant to the nations. It is the way back for all lost sheep: the Romanized ethnic Jew of Paul’s day, the cultural-nationalist of our own, and the wandering Gentile. Acts 15 extrapolates Edom—and by extension Rome—to the nations. The revelation at Mount Sinai, where the mixed multitude (ha-gerim) was saved, already prefigured this missional grafting process that unfolds through the Hebrew Scriptures and culminates in the Maccabean and apostolic eras. These became the “Mishnaic” or binding books for all peoples within the Empire—and indeed, for the world.

Just as then, so now, the Gospel—the Good News—announces the end of ungodliness and the arrival of spiritual globalism centered not on race or land but on Jesus of Nazareth, our Savior. This is the true purpose of Scripture: the redemption of humanity, not the enthronement of nations.

The Peril of Political Zionism

Yet Israel desired a king (1 Sam. 8) and thus joined the Gentile pattern of political power. That choice left the covenant community vulnerable to nationalism—today embodied in political Zionism and the nation-state ideology claiming the “Holy Land.” This error, though geographically specific, echoes in other nations, including the United States, where faith is too easily wedded to flag.

Both Reformed covenantal and dispensational frameworks—though seemingly opposed—cannot deliver us from this double bind. As long as Esau remains excluded from their theological imagination, the Abrahamic covenant remains truncated. We must not allow the coercive bilateralism of the Mosaic covenant to dictate the grander narrative. The promise that “in you all nations will be blessed” transcends Sinai; it began in Abraham’s household—with both Jacob and Esau—and must be read through the lens of Torat Edom.

The Lord’s promises to Abraham are not bounded by geography or political allegiance. They are spiritual, irrevocable, and oriented toward the Heavenly Jerusalem. Justice in the Holy Land will not come through national alignments but through faithful witnesses—believers supported by the global ekklesia—who understand that Edom’s restoration is itself the Great Commission, including the redemption of today’s “ethnic” and “cultural” Jews.

You may ask: Isn’t this an overly spiritual reading?

But I would answer: Don’t we all long to be called spiritual children of God by His grace?

Read 1 John: God is love, and that love is revealed fully in Jesus of Nazareth—the greatest demonstration of covenant mercy the world has ever known