The apologies toward other religions began, and emphasized from John Paul II to Francis. Still Rome’s motives are unclear while gestures toward the other religions shifted. Its view of itself as ‘the mother church’ continued by it patent absorbing and with a new language and compassion, all with the Virgin Mary at the center which implies its own centrality and here Rome has doubled down on its Marian devotion beyond the Theotokos. Thus, Judaism as the ‘cultivated olive tree’ and the centrality of Jesus Christ points to a revelatory religion system based not on relativism but on Scripture.

With the Eternal Son, Jesus of Nazareth the Christ, While Looking Under Every Rock …

Thou Shalt Not Covet

The apologies toward other religions began, and emphasized from John Paul II to Francis. Still Rome’s motives are unclear while gestures toward the other religions shifted. Its view of itself as ‘the mother church’ continued by it patent absorbing and with a new language and compassion, all with the Virgin Mary at the center which implies its own centrality and here Rome has doubled down on its Marian devotion beyond the Theotokos. Thus, Judaism as the ‘cultivated olive tree’ and the centrality of Jesus Christ points to a revelatory religion system based not on relativism but on Scripture.

Oracles of God

How should one understand the long history of spoken tradition behind the Oral Torah (Mishnah, Talmuds, et al.)? With so much emphasis on Hebrew texts and related languages—Aramaic, Koine (Judeo-Greek), Proto-Arabic (Judeo-Arabic), and others—should the textual paper trail serve as secondary and confirmatory rather than primary?

I believe so. The most revelatory text in this regard is the Septuagint (LXX), produced by Jewish scribes in the 3rd–2nd century BCE. It not only preserves elements of the Oral Torah but was given alongside the Written Torah. Its influence is evident throughout the New Testament, as seen in Jesus’ reading from Isaiah 61 in Luke 4:16. Despite speculative interpretations, the language of the passage tracks with the LXX.

Bart Ehrman, despite his skepticism, concludes that while New Testament texts contain many variations, they do not fundamentally change the meaning. However, his presupposition that Jesus was founding a new religion is flawed. The real issue arose later, as early Christians—both proselytes and “lost sheep” Jews—integrated into new communities. After Constantine outlawed the Bema seat synagogue in 333 CE, the authority of the Pharisees and Eastern synagogues was rejected in favor of a new, Romanized Christianity.

The dispersion of the late 1st century meant that Jewish communities maintained strong interactions with the East. Yet, those who upheld the ancient traditions were later slandered, marginalized, and persecuted by the victors of this newly formed religion. This fragmentation is well-documented by historical scholars, but what do Jewish sources say?

Jesus himself affirms the authority of the Pharisees in Matthew 23: “Obey them, for they sit in the (Bema) seat of Moses. Do as they say, but not as they do.” Paul echoes this sentiment in Acts 15. However, Jesus also rejected the extremism of groups like the Zealots, affirming Caesar’s authority and urging discernment in choosing one’s allegiance.

Paul’s warning in Titus against “fables and the traditions of men” is often misunderstood. He never directly quotes the Enochian corpus, though some of its ideas were known. Ultimately, these texts should be seen as speculative and fantastical—much like a Frank Peretti novel or modern prophetic fiction, akin to C.S. Lewis and Tolkien.

The real deviation from authentic Jewish tradition came with the rise of sectarian groups like the Shammai Pharisees and Sadducees, whose political alignments overshadowed spiritual truth. The same is true today with forms of Judaism that reject the role of Jesus of Nazareth.

For Hebrews from the nations, the purpose of the Oral Torah is to graft into believing Israel—the cultivated olive tree. This faithful remnant has existed even before Abraham, with the Anshei HaShem (Men of the Name). Engaging with Constantinian Christianity, German higher criticism, or modernity is futile if one does not seek out the ancient faith.

Let us not build on the shifting sands of fragmented Christianities that fail to grasp the singular revelation and mission of our Lord. He has visited His people many times and does not change with dispensations. Nor should we marginalize the Pharisaic tradition of Gamaliel, whom Paul followed.

Evangelical Zionist dispensationalism, while professing love for the State of Israel, often misrepresents the faith, while Reformed covenantalism claims the Church is the true Israel. Yet both, in their extremes, assume the right to define Jewish identity for the very people entrusted with the oracles of God. Instead, we must join together to be the righteous ones in this world by properly understanding our authoritative textual history—passed down through the system of oral teaching, with the written text serving as a secondary yet indispensable witness.

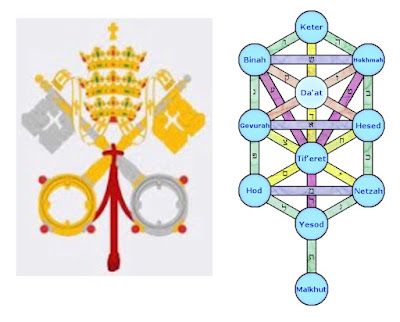

For Messianic Hebrews, however, the text is anything but secondary. Inerrancy is not merely textual perfection—it reveals a mathematical miracle, a divine order preserved through ancient orality. This understanding aligns with the long, legitimate tradition of Kabbalah, which, far from being an ethnic exaltation, carries a trail of blood—a witness to the cost of preserving divine truth.

Symmetry: Judaism and Christian Faith Not Christianity

Educated at the Volozhin Yeshiva, the most prestigious Jewish institute of higher learning in the nineteenth century, Soloveitchik was deeply immersed in classical Judaism. Comparisons between him and Jacob Emden (1697–1776) are reasonable, as both acknowledged the morality of Christianity and rejected the notion that Jesus came to abolish the law for Jews. However, the resemblance is superficial. Unlike Soloveitchik, Emden, though well-versed in the Gospels (which he frequently cited), never wrote extensively about them, nor did he go as far as Soloveitchik in arguing that Judaism and Jesus’ faith—better termed the Christian faith—were fundamentally indistinguishable.

Soloveitchik’s writings reveal a passionate, candid, and sincere thinker grappling with what he believed was a millennia-old misunderstanding between Judaism and Christianity. His work provides a rare glimpse into the mind of an Eastern European Jew confronting modernity, challenging long-standing Jewish assumptions about the supposed irreconcilability of the two faiths. He grants Christianity its historical and theological legitimacy, offering a perspective on Jesus of Nazareth untainted by the accretions of folk distortions and the controversies embedded in Talmudic polemics.

However, where Soloveitchik takes a Maimonidean turn, I must diverge. His attempt to reconcile Maimonides (Rambam) with the Litvak Perushim was met with criticism, particularly from within Lithuanian Jewry, though some Hasidic groups—most notably Chabad—embraced aspects of this approach. Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, encouraged such studies within the remnants of Yiddish Judaism, seeking to revive a rigorous intellectual engagement with Maimonides’ thought.

Yet, Maimonides’ rationalist framework stands in stark contrast to the deeply mystical tradition of Kabbalah, which he explicitly rejected. His Guide for the Perplexed aligns more closely with classical theism, mirroring the Aristotelian logic later systematized in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica for the Catholic Church. Just as Aquinas sought to create a symmetrical system based on Aristotle, Maimonides did the same within Judaism—an effort that, while intellectually formidable, ultimately distances itself from the organic, revelatory nature of biblical and rabbinic tradition. His metaphysical approach, akin to the analogia entis developed through Meister Eckhart, finds resonance in Western Scholasticism but remains incompatible with the inner workings of post-Second Temple Judaism.

This is where Soloveitchik, despite his rationalist leanings, inadvertently brings us back to a crucial safe haven: the New Testament text itself. While his commentary may at times feel earthy and unfamiliar, it opens a door to honest engagement with the words and mission of Jesus of Nazareth, free from centuries of polemical baggage.

The history of the twentieth century was not kind to Soloveitchik’s predictions. As a result, he and his work faded into obscurity—until now. His writings deserve renewed examination, not necessarily as a blueprint for merging Judaism and Christianity, but as a bold attempt to bend history toward coexistence and mutual understanding. He sought to dismantle the animosity and lingering hatred that have long divided the two faiths, yet ultimately, true reconciliation can only be found in the one name under which salvation is given: Jesus the Christ.